Art in America, June 2005 by Pepe Karmel

A few years ago, my son and I took the shuttle bus from Orlando to Disneyworld. As we drove through the flat Florida landscape, I noticed that the woman sitting next to me was wearing the ID tag of a Disney employee. She was from southern Germany, it turned out, and worked in the Bavarian beer garden at Epcot Center. Wasn't it strange, I asked her, to work in a replica of the place she came from? "The town I grew up in was bombed during the war, and then rebuilt to look exactly the same as it did before," she said. "So it isn't really that different."

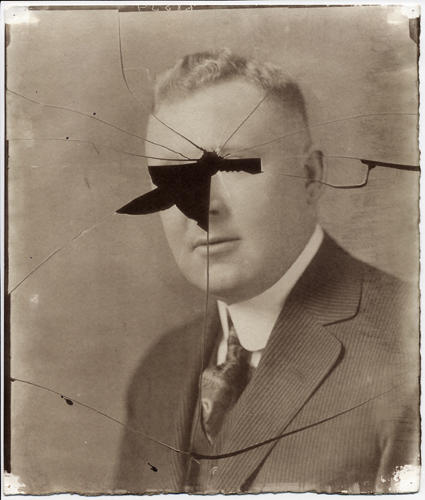

Like the German pavilion at Epcot Center, Thomas Demand's photographs offer a cleaner, heater version of the real world. At first glance, they appear to be straightforward records of unremarkable locations: offices, auditoriums, hallways, kitchens, bathrooms, staircases, stadiums and gardens, the familiar sites of mass society. It seems mildly perverse to give modest documents such heroic presentation: enlarged to mural scale and laminated to gleaming sheets of Plexiglas. And there is something off about the scenes in Demand's photographs. They record the traces of human activity, but no people appear in them. The surfaces are too smooth, the edges too sharp. Sometimes things are damaged, but they never betray the wear-and-tear of daily life. To walk through the retrospective of Demand's (mostly very large) photographs (1993-2004) at the Museum of Modern Art was to enter an unsettling alternate universe.

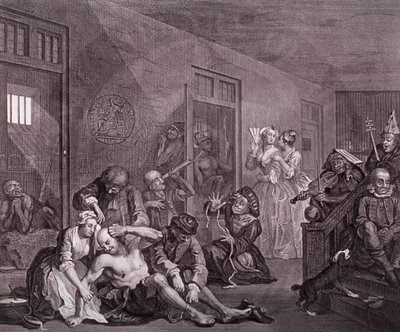

Like Epcot Center, everything in Demand's work is a fake, a meticulously constructed replica in paper and cardboard. Unlike Epcot Center, Demand's pictures often lead the viewer into a troubling confrontation with history, both German and international. A 1994 photograph with the anodyne title Room shows a conference room in a shambles: table collapsed, windows askew, moldings tumbled to the floor, chairs overturned. This is Demand's re-creation of the military conference room where Count Stauffenberg attempted to assassinate Adolf Hitler on July 20, 1944. Four people were killed and the room was demolished, but Hitler survived.

Room, 1994

"Tunnel"- stills from a video, a recreation of the scene of Princess Diana's death

Sink, 1997

Space Simulator, 2003

Archive, 1995

Gate, 2004