One such project, titled Fauna, is the story and "archive" of one of Fontcuberta's alter egos, Professor Peter Ameisenhaufen, a zoologist. Fauna documents Dr. Ameisenhaufen's childhood and career, and speculates about his mysterious untimely death. The bulk of the project concerns the controversial discovery of a number of previously unknown species of animals.

The Fauna project is more fully explained here and here.

Some exerpts from the project-

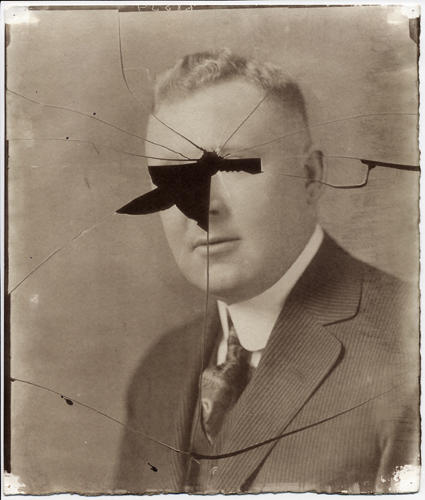

Peter Ameisenhaufen was born in Munich on May 5, 1895, as the first child of the explorer, big-game hunter, and safari guide Wilhelm Ameisenhaufen, pictured above (b.1860 in Dortmund, d.1914 in Dar es Salaam) and his wife Julia (b. 1873 in Dublin, d. 1895 in Munich).

Peter and his sister spent a happy childhood in Dortmund in the care of their aunt. They attended a Catholic school, where Peter was remarkable for his exceptional diligence. When he was ten years old, he traveled to his father in Africa for the first time.

Hermafrotaurus Autositarius- Not a particularly sociable animal, but pacific; it lives in the foothills and preferably in rocky areas. Its diet consists of reptiles and small wild rodents. Its pseudofalse hermaphroditism results in complete monogamy, and sexual relations with itself are quite frequent. Given the division of functions between the two branches of the spinal chord, Hermafrotaurus Autositarius could be considered to be two differentiated parts converging in a single head. One of these parts is female and particularly sensitive to gastronomical and emotional stimuli (love for its offspring). The other part is male and very sensitive to sexual stimuli (the female part is constantly in heat) and to somnolence (the male part is almost always asleep, unlike the female part, which suffers from total insomnia).

Alopex Stultus- An herbivorous animal, completely inoffensive and very timid. When it senses the proximity of an enemy, it finds a shrub of the species Antrolepsis Reticulospinosus and digs a hole in the earth, into which it sticks its head, leaving the rest of the body suspended in a vertical posture in an attempt to mimic the shrub. Unfortunately, the outcome is not particularly satisfactory and both men and predators usually capture it at this point.

Cercopithecus Icarocornu- the sacred animal of the indigenous Nygala-Tebo tribes, for whom it represents the reincarnation of Ahzran (he who came from heaven). The females give birth inside a large cabin in the village to which only the great shaman has access. The baby animals remain inside the cabin until they have completely developed their ability to fly, at which point the tribe celebrates a lavish ceremony during which Cercopithecus undergoes an operation in which it is grafted with the skin of the silver fish of the Amazon, which covers all of the pectoral and abdominal zone. Once this has been done, the animal is set free, although it never strays very far away from the village, and participates by its presence in all of the sacred festivals of the NygalaTebo. During these festivals the animal is given a spirituous beverage which it drinks eagerly, sinking into a state of complete inebriety, at which point it begins to flap its wings so madly that it hovers in mid-air with its body immobile, singing like one possessed.

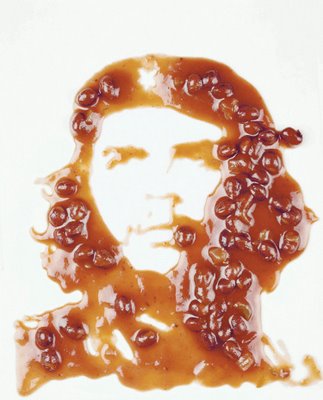

Centaurus Neardentalensis

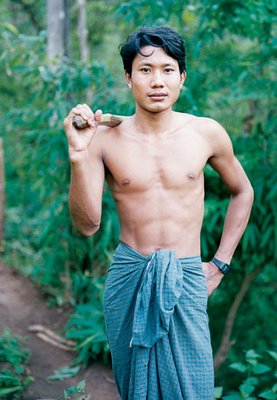

Micostrium Vulgaris- A gregarious animal which lives in colonies of varying numbers of individuals (6-30). Extremely sociable, it does not flee human contact and has shown itself to be playful and affectionate. It is only disturbed by the sound of the human voice, so it must be approached in complete silence. It has a tremendous capacity for mimicry in semiaquatic environments. It is worth noting that it makes use of "weapons" (normally very hard sticks or branches which can be found on the banks of the river) to capture the fish which make up its diet. The courtship ritual is particularly curious. The male follows the female for three days, uttering the characteristic cry of "Kree-ee-ee- ah Klook," to which she replies with vertical leaps and pirouettes. On the fourth day the female (which is three times smaller than the male) crawls completely inside the shell of the male and mating (which lasts some three seconds) occurs. During this brief period of time the shell of the male emits a tremendously intense whitish blue luminous radiation which makes it an easy target for birds of prey.

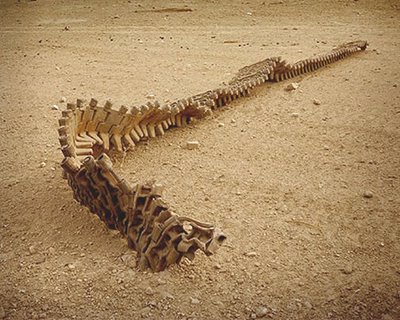

Solenoglypha Polipodida- Extremely aggressive and venomous, it hunts for food and also for the pleasure of killing. It is quite rapid and moves forward in a curious and very rapid run, thanks to the strong musculature of its 12 paws and the supplementary impulse which it obtains by undulating all of its body in a strange aerial reptation. When facing its prey it becomes completely immobile and emits a very sharp whistle which paralyzes its enemy. It maintains this immobility for as long as the predator needs to secrete the gastric juices required to digest its prey, which can vary between two minutes and three hours, as determined by the size of the victim. At the end of the whistling phase, Solenoglypha launches itself rapidly at its immobile prey and bites the nape of its neck, causing instantaneous death.

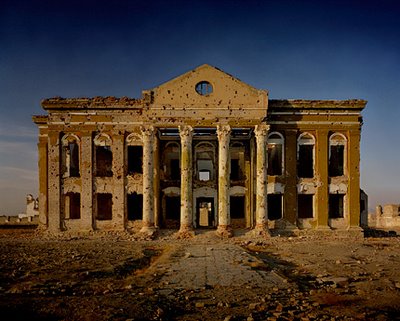

Felix Penatus

A stuffed specimen which was found without any documentation in the professor's research.

Questions:

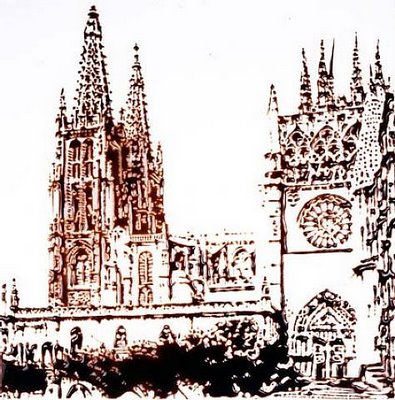

- What are the visual elements of Fontcuberta's work that make it convincing as a historical document? What about the written elements?

- How does Fontcuberta's work raise questions about the assumed "truth" of the photographic image?

- How would you compare and contrast this work with that of Yinka Shonibare, from Ch. 2?